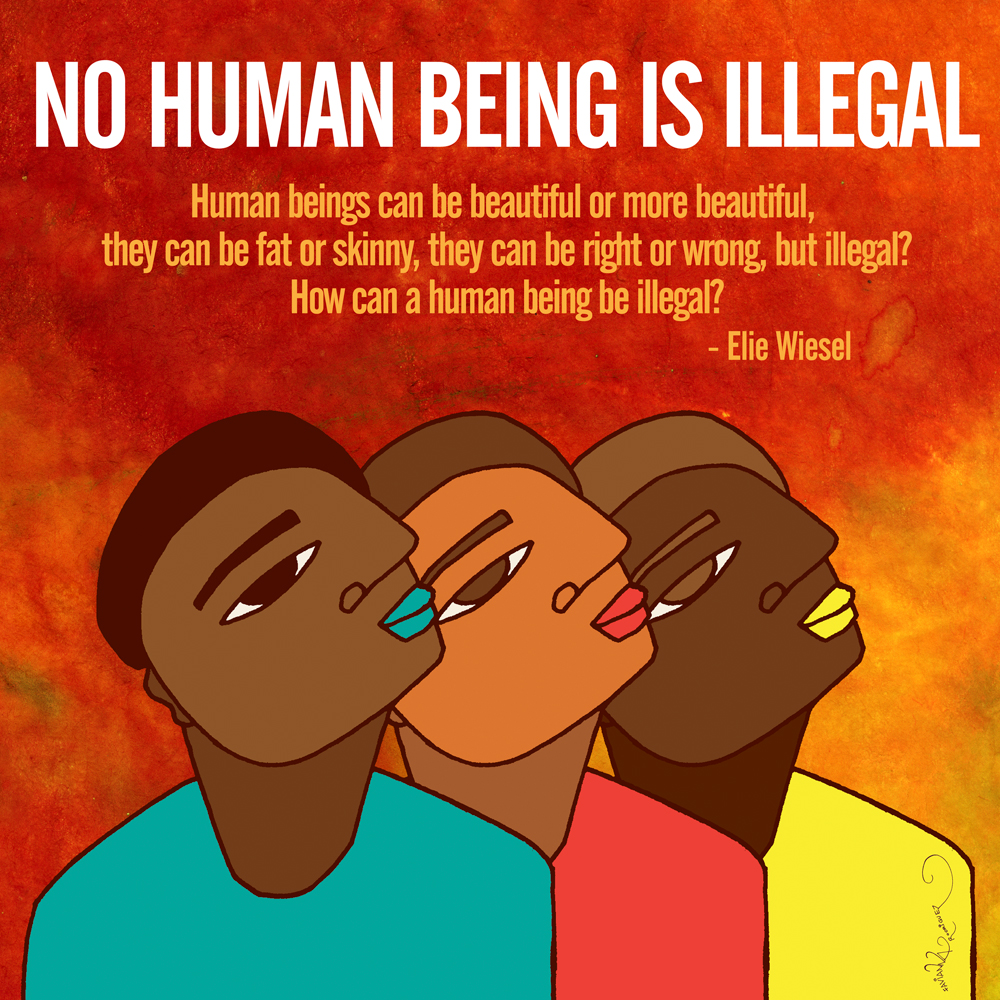

Ningún ser humano es ilegal.

Los seres humanos pueden ser bellos o más bellos, pueden ser gordos o flacos, pueden tener razón o estar equivocados, pero, ¿ilegales? ¿Cómo puede ser ilegal un ser humano?

- Elie Wiesel.

La renombrada poetisa, feminista, teórica y activista negra Audre Lorde dijo una vez: “No existe una lucha de un solo asunto porque no vivimos vidas de un solo asunto”. Esto es exactamente lo que representan el arte, la política y la voz de Favianna Rodríguez.

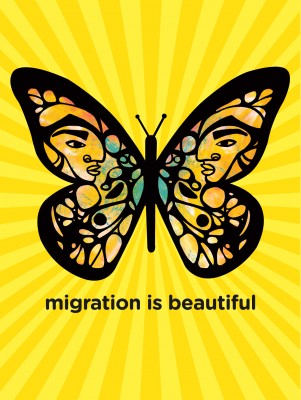

Hija de migrantes peruanos en Estados Unidos, ahora con 36 años, es una fuerza a tener en cuenta. Es incansablemente activa en muchas luchas: de migrante, de mujeres, derechos LGBT, raciales, de clase, ambientales y justicia alimentaria. La lista es interminable y viva y crece día a día. Aunque sobre todo, es una artista —una vocación que cree que engloba todo lo que cree y por lo que vive.

Favianna habló con Global Voices vía Skype desde su casa en Oakland, California. Su sonrisa es cálida y su tono es insistente. No tiene mucho tiempo que perder, aunque es generosa y ocupada. Hablamos con ella sobre su vida, su arte y su política.

Global Voices (GV): ¿Cómo te nació la consciencia? ¿Recuerdas un momento en particular? Siempre recuerdo esta frase del título de la biografía de Rigoberta Menchú.

Favianna Rodríguez (FR): I grew up in a migrant family, my family is from Perú, I am first generation. I would notice there would be a lot of racism directed at my parents. At a young age I was acting as a translator for my parents. I always felt that we were outsiders. When we moved to a Latino community, I didn’t feel this so much, but when we moved, it was extremely evident. I had curly hair, I was different, I never felt I belonged.

When I went to high school I started organizing around Latino issues. They would talk to me about racism and how young Latinos were viewed as gangsters. The narrative about my fellow peers was always very negative. Then I started learning about the Mayas, the Aztecs, and the contributions of so many Latinos to the United States. We organized the day of Latino students, I founded the first Latino club in my high school. This was also at the time in of Proposition 187, the first time that a state had introduced an anti-migrant piece of legislation. It was horrible. When I began to understand systemic racism, it changed my whole worldview.

It was a combination of living in a very anti-Latino time (the 1990s), but also finding the power of collective action that helped me learn love myself. I began to learn our history. I didn’t feel part of the fabric of this country, and yet we were. I hadn’t learned how much economically we shaped this country.

Favianna Rodríguez (FR): Crecí en una familia migrante, mi familia es del Perú, soy primera generación. Me di cuenta de que había mucho racismo dirigido a mis padres. De chica, me desempeñaba como traductora de mis padres. Siempre sentí que éramos ajenos. Cuando nos mudamos a una comunidad de latinos, no sentí mucho esto, pero cuando nos mudamos, era extremadamente evidente. Era crespa, era diferente. Nunca sentí que perteneciera.

Cuando estaba en secundaria, empecé a organizarme en torno a asuntos latinos. Me hablaban de racismo y cómo a los latinos jóvenes se les veía como pandilleros. La narrativa acerca de los que eran como yo siempre fue muy negativa. Entonces empecé a aprender sobre los mayas, los aztecas, y las contribuciones de tantos latinos a Estados Unidos. Organizamos el día de los estudiantes latinos. Fundé el primer club latino en mi secundaria. Esto fue también en la época de la Proposición 187, la primera vez que un estado presentó una legislación antimigrante. Fue horrible. Cuando empecé a entender el racismo sistémico, cambió toda mi forma de ver el mundo.

Fue una combinación de vivir en un tiempo muy antilatino (los años 90), pero también de encontrar el poder de la acción colectiva que me ayudó a aprender a quererme. Empecé a aprender nuestra historia. No me sentía parte del material de este país, y sin embargo lo éramos. No sabía cuánto habíamos contribuido económicamente este país.

GV: ¿Crees que ese clima antilatino en Estados Unidos ha cambiado?

Favianna Rodríguez.

FR: What I think has changed is that we have built a political culture, but we are still very invisible.

FR: Lo que creo que ha cambiado es que hemos construido una cultura política, pero seguimos siendo muy invisibles.

GV: Tu arte y política combinan derechos migratorios, derechos de mujeres, feminismo, derechos sexuales, derechos LGBT, justicia medioambiental, justicia racial, justicia de clase y más. ¿Puede el activismo de justicia social escoger y seleccionar asuntos?

FR: First, in many ways I am responding to issues that have affected me as a human being, a migrant, a woman, having had an abortion, being a woman of color in the art world, I live these experiences in my work and art. We experience life in a very different way. What I create is a reflection of a different experience, what white men create is another experience. There is a value from creating that stems from lived experiences. I grew up seeing how immigrants diets changed as soon as they came to the US, for example, this made me realize that all of this was connected, food, labor, capitalism, women.

Art has the power to do all of this because art by nature is intersectional. Politics tend to be fragmented, directed at particular people, and to me art is about life. When you are an art maker, a musician, you are not looking to tell the story of one person, but of human beings. On the other hand, political organizing can be very specific. I think I am able to easily move between worlds because I am an artist, and I am not attached to a particular issue. I combine narratives.

FR: Primero, de muchas maneras, estoy respondiendo a asuntos que me han afectado como ser humano, migrante, mujer que ha tenido un aborto, una mujer de color en el mundo del arte, vivo estas experiencias en mi trabajo y arte. Experimentamos la vida de una manera muy diferente. Lo que creo es un reflejo de una experiencia diferente, lo que los hombres blancos crean es otra experiencia. Hay un valor en crear que surge de las experiencias vividas. Crecí viendo cómo las dietas de los inmigrantes cambiaban en cuanto llegaban a los Estados Unidos, por ejemplo, esto me hizo dar cuenta de que todo estaba conectado: comida, trabajo, capitalismo, mujer.

El arte tiene el poder de hacer todo esto porque el arte por naturaleza es interseccional. La política tiende a estar fragmentada, dirigida a personas en particular, y para mí el arte es sobre la vida. Cuando haces arte, música, no buscas contar la historia de una persona, sino de seres humanos. De otro lado, organizarse políticamente puede ser muy específico. Creo que puedo moverme fácilmente entre mundos porque soy una artista, y no estoy ligada a un asunto en particular. Combino narrativas.

GV: Uno de los temas que está presente en tu arte y política es erradicar los tabús en la sexualidad de la mujer, y reconocer el poder y la belleza de la sexualidad. ¿Cuáles son las intersecciones entre sexualidad y derechos sexuales y otras formas de activismo, como derechos de migración y justicia medioambiental?

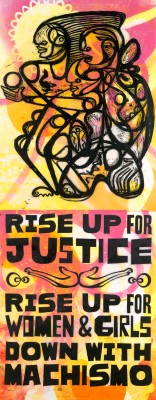

FR: I’ve come to the realization that liberation begins with our bodies. We need complete control and autonomy over our bodies. The core of our independence is to have governance over our bodies. We are living in a time in which women’s bodies are being more and more discussed in politics, and abortion rights are being taken away, there is a real threat to our autonomy. Love and relationships are at the center of how we build our societies, and if we do not have a feminist view of how to build societies, with women and girl’s autonomy and freedom at the center, we cannot build a better world. Sex trafficking, for example, is one of the industries of most growth in the world. There is a belief that women’s bodies can be sold and objectified. If you look at Juarez, and other contexts of massive violence against women, the core is the exploitation of women’s bodies. This is why any transformation must put women’s sexual rights at the center.

In Latin America this is a priority. They are at the front line, they don’t call it reproductive rights, but sexual justice. This is not about reproduction but about sexual and gender justice. There is a stereotype that Latin American women are repressed, and that is not true. They include sexual workers in their feminist activism, and that is really important.

FR: Me he dado cuenta de que la liberación empieza con nuestro cuerpo. Necesitamos completo control y autonomía sobre nuestro cuerpo. El meollo de nuestra independencia es tener gobierno sobre nuestro cuerpo. Estamos viviendo un tiempo en el que el cuerpo de la mujer se discute más y más en política, y se están arrebatando los derechos del aborto, hay una real amenaza a nuestra autonomía. El amor y las relaciones están en el centro de cómo construimos nuestras sociedades, y si no tenemos una visión feminista de cómo construir sociedades, con la autonomía y libertad de mujeres y niñas al centro, no podemos construir un mundo mejor. El tráfico sexual, por ejemplo, es una de las industrias de mayor crecimiento en el mundo. Hay una creencia de que el cuerpo de la mujer se puede vender y convertirse en objeto. Si miras a [Ciudad] Juárez, y otros contextos de violencia masiva contra la mujer, el eje es la explotación del cuerpo de la mujer. Es por eso que cualquier transformación debe poner los derechos sexuales de la mujer en el centro.

En Latinoamérica esto es una prioridad. Está en primera línea, no lo llaman derechos reproductivos, sino justicia sexual. No se trata de reproducción sino de justicia sexual y de género. Hay un estereotipo de que la mujer latinoamericana está reprimida, y eso no es verdad. Incluyen a trabajadoras sexuales en su activismo feminista y eso es realmente importante.

GV: ¿Cómo te identificas? ¿Sientes la necesidad de identificarte?

FR: I identify myself as an artist, first and foremost, before I say I am a woman. Because for me art is being a critical thinker. I think women’s and immigrant issues are issues of humanity, and even though I embrace that, I actually want to be seen as an artist. Gender can also be like a jail. I hate that when I do street art I have to be mindful of my surroundings, be careful, and I don’t like that some things are associated with my gender. Artists are risk takers and truth speakers. My calling in life is to create. And artists should be challenging the status quo.

FR: Me identifico como artista, por encima de todo, antes de decir que soy mujer. Porque para mí, el arte es ser un pensador crítico. Creo que la mujer y los problemas de inmigrantes son asuntos de humanidad, y aunque lo acepto, quiero que me vean como artista. El género también puede ser como una cárcel. Odio eso cuando hago arte callejero y debo tener en cuenta lo que me rodea, tener cuidado y no me gusta que algunas cosas se asocien con mi género. Los artistas toman riesgos y dicen la verdad. Mi llamado en la vida es crear. Y los artistas deberían desafiar el status quo.

GV: He descubierto un poderoso movimiento en línea de inmigrantes en Estados Unidos que hacen arte, sobre todo grabado. ¿Hay una tradición histórica de esto en Estados Unidos? ¿Crees que hay un “boom” en este momento de arte político migrante en Estados Unidos?

FR: Yes, absolutely, and believe it or not one of the most powerful printmaking tradition comes from Puerto Rico, and also Mexico and Cuba. I think printmaking is so powerful because it allows for multiplicity. In the 60s and 70s it was art in the service of liberation and education. The “Taller de Gráfica Popular” in Mexico was all about the creation of the multiple, moving away of valuing one work of art, and instead thinking that art should be distributed and shared. I would call it the art of the multiple, and now it also lives in the online world.

FR: Sí, absolutamente, y lo creas o no, una de las tradiciones más poderosas de grabado viene de Puerto Rico, y también de México y Cuba. Creo que el grabado es poderoso porque permite la multiplicidad. En los 60 y 70 era arte al servicio de la liberación y la educación. El “Taller de Gráfica Popular” en México fue sobre la creación de lo múltiple, pasar de valorar un trabajo de arte a pensar que el arte debe ser distribuido y compartido. Yo lo llamaría el arte de lo múltiple, y ahora también vive en el mundo en línea.

GV: ¿Cómo ha contribuido Internet con tu activismo y tu arte?

FR: My evolution as an artist began because of the Internet. In those very first days, adobe photoshop 1.0 and Illustrators gave me a whole set of new tools to create. I realized that I could have my work on a page for the whole world to see. The Internet was an open space to have your content and connect with the world. Also the DIY [Do It Yourself] culture really helped. I was able to learn so much. It totally shaped how I do my work, I believe in technology as an important part of my work.

FR: Mi evolución como artista empezó gracias a Internet. En esos primeros días, adobe photoshop 1.0 e Illustrators me dieron toda una gama de nuevas herramientas para crear. Me di cuenta de que podía tener mi trabajo en una página para que todo el mundo lo viera. Internet era un espacio abierto para tener tu contenido y conectarte con el mundo. También la cultura DIY [Hazlo Tú Mismo] realmente ayudó. Pude aprender tanto. Dio forma a cómo hago mi trabajo. Creo en la tecnología como una parte importante de mi trabajo.

1 comentario

¡Gracias por la traducción Gabriela!