Foto original de Vladimir Varfolomeev. Conmemoración del terrorismo en Nord Ost. 27 de octubre del 2013. CC 2.0. Editado por Kevin Rothrock.

Hace no mucho tiempo, un grupo armado de militantes islamistas tomaron un teatro en una gran ciudad europea durante un evento con aproximadamente mil personas presentes. Luegode que fuerzas especiales finalmente asaltaron el edificio y mataron a los secuestradores, más de una centena de civiles yacían muertos. Esto fue el asedio de Nord-Ost de 2002, en Moscú, cuando al menos 40 chechenos separatistas tomaron como rehenes a 850 personas en el Teatro Dubrovka. El asedio duró cuatro días y tres noches, resultando en la decisión controversial de las fuerzas especiales de Rusia de llenar el teatro con gas knockout, que accidentalmente mató a 130 rehenes.

Con los trágicos ataques en París, a inicios de noviembre (particularmente la masacre en el Teatro Bataclan, que cobró 89 vidas), muchos rusos están recordando ahora cómo las balas y bombas de los terroristas plagaron su propia capital hace trece años.

El 15 de noviembre del 2015, la bloguera Anastasia Nikolaeva publicó una entrevista con un hombre que dice ser uno de los rehenes que sobrevivió el asedio de Nord-Ost. El hombre, otro usuario de LiveJournal que escribe bajo el nombre Maksi2278 (y proporcionó el escaneo de los papeles del alta del hospital de octubre de 2002), describió cómo fue estar en cautiverio por días, cómo se llegó a sentir sobre los terroristas que prometieron asesinarlo y cómo la experiencia lo ayudó a dar forma a su apoyo a la intervención militar rusa en el Cáucaso Norte. Runet Echo presenta la entrevista de Nikolaeva traducida del ruso.

Anastasia Nikolaeva: Were you there the whole time? Were you alone? What happened with the use of the gas? As I understand it, you believe that the Russian special forces actly correctly? How were you helped afterwards?

Maksi2278: Yes, I was there from the very beginning all the way up to when the theater was stormed.

I wasn’t there alone—I was with two female friends. One of them died. Her name was Masha Panova. You can Google it. My other friend survived, and she’s fine now.

Using the gas was the right call, I think. And I think our special forces handled themselves like true professionals. Admittedly, I didn’t see the assault itself. I passed out. The last thing I remember is how this smoke started pouring out from the orchestra pit, and Mr. Vasiliev ran over there with a fire extinguisher. Everyone thought there’d been a short circuit (there was a bathroom in the orchestra pit and things had gotten quite wet).

The next thing I remember is waking up in intensive care at Hospital Number 13. Clinically, I’d actually died, but they were able to revive me.

At the hospital, everyone who could—even some patients—were helping out. It was pretty close to the Dubrovka Theater—walking distance even—and it’s where they brought most of the hostages [after they were rescued]. My friend was brought to Sklifosovsky Hospital, which is much farther away.

So everyone was helping out. Like they were helping to carry people from place to place, and so on. When I woke up, all around me were several doctors, and I remember that I wanted a glass of water desperately and needed to use the bathroom. I couldn’t go in a bedpan, though, and I couldn’t make it to the toilet on my own. A couple of women doctors basically had to carry me over their shoulders to the bathroom. :)

After a few hours had passed, I started feeling almost normal again. They kept me there another couple of days, and then I was released. The hospital was cordoned off. There were even special forces guys with automatic weapons in the hallways.

From what I understand, they didn’t take any hostages [at the concert hall in Paris]. The attackers just slaughtered those were were present. At the Nord Ost, the authorities aren’t criticized for storming the theater, per se, but for failing to save more hostages, which they theoretically could have.

Yes that’s true, but there were several dozen experienced fighters at Nord Ost, not four youngsters. The Nord Ost terrorists also mined the entire theater and controlled not just the main hall, but the whole building and even some of the street.

Could the authorities have saved all the gas victims? Who the hell knows. Here you’ve got to take into account the situation and the condition of the hostages. On the one hand, you need absolute secrecy, and for God’s sake you can’t let the journalists sniff out the preparation for the assault. On the other hand, the hostages had been in the building for a very long time, sitting in uncomfortable chairs in the same position, without food and without even enough water. For instance, I only got up and went to the bathroom twice during the whole thing. And the stress was absolutely monstrous, of course. In other words, everyone was extremely weakened. Could the authorities have taken all this into account? Could there have been more ambulances and first aid ready, with roadways to hospitals cleared, and enough doctors on staff? Sure, probably. And maybe not. In the end, they saved 90 percent of the hostages and that’s an enormous success. We were very lucky.

It wasn’t the people who organized our rescue or the “slow-moving” medics who killed the victims—it was the armed men and women who came to our peaceful city, to a theater, to kill civilians. Did you know that most of the people in the theater audience were women and children?

Of course, the situation [at the concert hall in Paris] is very different, but the fact is that three of the four terrorists blew themselves up, after they fired all their ammunition at the crowd and at police officers. In other words, the assault against these men failed. Of course, it’s impossible to blame [the police] for this—I think they did everything they could.

It just seems to me that, by the results alone, these two terrorist attacks are similar. Of course, the situations were different.

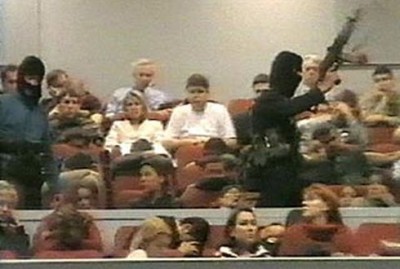

Screenshot from television footage of Nord-Ost Siege. Circulated anonymously online.

I want to ask you: did you see anything “human” in the terrorists [who seized the Dubrovka theater]?

Yes, I most definitely saw some humanity. I was sitting in the fifteenth row on the ground level, and not far from me stood a young woman suicide bomber. I tried to talk to her, and a couple of times she even answered me, but the older ones noticed and said something to her, and she stopped responding to me.

I remember her eyes. Afterwards, I often dreamt of them.

I talked to her about letting the women and children go: “What did they ever do to you? If you’re burning so bad to fight, take it to our officials. They’re the ones who started the war.”

To this, she said, “Our families—everyone’s families—have died in the war that you started. They weren’t guilty of anything, either, and there were women and children among them, too.”

Then I said, “Well, let’s say you kill us all right now. Can you imagine what the Russian Army, in retaliation for our deaths, would do next?” And this suddenly had an effect on her. She was thinking about it, and then they shouted her out of it.

There was another terrorist there, Yasser, who walked around without a mask, and was sort of a “good cop,” as opposed to this complete thug they called “Abubakar.” Yasser talked to people like a normal human being, and he listened carefully to people who, for instance, were asking something on behalf of the sick. But if Abubakar said anything, it was just a bunch of threats: we’ll cut your heads off, you’re all gonna die, you swine, I hate you, and so on. And on the first night, he executed a young woman. They just stood her up in the exit way and he emptied his automatic weapon into her.

I also remember hearing a conversation between other hostages and a woman suicide bomber. She grabbed a mobile phone from one of the hostages and said, “Hmm, this thing is cool. How nice that you have such phones, and we don’t.” The thing is, she was genuinely impressed and honestly thought it was “cool.” This is back when mobile phones were still really basic.

And there was their commander, Movsar Barayev. Now, at the time, we were completely overwhelmed and we didn’t know it was Barayev. We just heard them call him “Movsar.” The name sounds strange to Russian ears, and I remember thinking it must have been his nickname—something like “Mozart.” :) Generally speaking, he was relatively calm—the way he behaved. He wasn’t especially rude, and he didn’t kill or beat anyone himself.

Maybe that’s how we saw that not all the terrorists were complete thugs, and “Stockholm Syndrome” set in, and people started believing that they could reach some deal with the terrorists and we could all survive, if right now we could send just one message or make just a single phone call.

I’ll tell you about another moment: after a failed assault on the theater (on the first morning, they sort of tried to storm the building), they blew up a wall somewhere and knocked out some windows, not in the main concert hall, but nextdoor. And there was a strong draft, and it was very cold. The hostages begged for clothes from the coat check. Eventually, [the terrorists] gave in, and a few guys brought the coats over, dropped them in a pile where we were sitting, and started handing them out. I saw my coat and I stood up, saying, “Please give me that one—it’s my coat.” Then one of the terrorists poked me with his automatic weapon and said (verbatim), “You’ll manage without it, buddy. Take a seat. You’re pretty enough already.” :) And I really was quite “dressed up.” I was in a good suit. :) I’m not sure what you make of it, but at the time we all thought this was pretty funny, and people all around had a good laugh.

And I can tell you about another time: there was a moment in the main concert hall, when suddenly in the radio room (the window above the auditorium, where the theater’s operator sits) the news broadcast stopped and a rather cheerful song by the band Scooter started playing. And people in the theater noticeably started to perk up—some of them were even singing along. But this didn’t last long, of course.

It’s just impossible to imagine: people are living, while there’s still life, and they’re even singing along to the radio… I read about this before, but I’ve never heard it before from an eyewitness.

Well, we were there for a very long time. We didn’t sleep and we didn’t eat. We just sat there and waited. Mostly it was just numbness and panic attacks, when you lost feeling in your feet or you had a spark of hope that we’d be rescued, and you’d start twitching all over. You’d start talking quietly with someone next to you, but you’d put as much energy into speaking in a whisper as you’d normally use to scream. You’d think over all your options, choose every word carefully, listen insatiably to every word the terrorists uttered and every phrase that you could overhear on the news. Then the apathy would return, and there’d suddenly be more gunfire. For a moment, people would fall to the ground between the rows of seats, and Barayev would yell at us to stay standing, otherwise they’d execute anybody who ducked down. But everyone would still fall to the ground. It was like an instinct.

Screenshot from television footage of Nord-Ost Siege. Circulated anonymously online.

Did you find yourself having any feelings of sympathy toward the terrorists? Maybe something like, “Damn, this girl’s actually really cute.” Was the girl cute, by the way?

Her face was covered. Only her eyes were visible. They were hazel and very beautiful. She was clearly very young. But I didn’t feel any sympathy, except maybe toward Yasser. Thanks to him, we got bottles of water, for instance. I didn’t feel hatred, either. I experienced only two things: fear and the desire to survive. My brain was racing at a hundred miles a minute, searching for ways to live. And the absolutely strangest ideas came into my head: escape plans, plans to get the hostages together to attack the terrorists, or even a way to give the terrorists what they wanted, so they’d let us go.

Although, they took the men’s passports and looked at our military service records. If you were in the army reserve, it meant you’d be first in line to be shot. That’s what they said to us, so I didn’t have much hope of surviving.

Was there anyone without a passport? What happened with these people?

Not only were there people without their passports, but there were people who hid them. Some men had military cards with them, not passports, and they either hid them or tossed them away. I myself saw a few military cards tossed into the orchestra stalls from the balcony. You see, the terrorists promised to execute or behead any soldiers or KGB agents on sight.

In practice, if someone was missing his passport, they’d just keep an eye on that person and promise to kill him later. But they never ended up doing this. There were no executions without clear reasons. They just never worked up to it, though they were finally ready to start executing hostages, just before the police raided the theater. If memory serves correctly, they wanted to shoot 10 people every hour. But they executed no one without a reason.

What do you mean “without a reason”? They shot and killed a young girl, you said…

Well, if you ask me, there was a reason. As I found out later, this girl had come to the theater after she learned about the hostage crisis. They caught her near the main doors and took her into the concert hall, where they brought her to Movsar Barayev, who started to interrogate her in front of everyone. The terrorists thought she was one of the FSB’s scouts. Later we learned that she was just someone who lived nearby—from basically the neighboring building. But none of this was clear then, and the terrorists didn’t believe a single word she said. At the same time, she made a show of defiance and bravery, acting like she was on the verge of hysteria.

The dialogue was something like this:

Movsar: Who are you and why did you come here?

Girl: And who are you and why did you come to my city?

Movsar (to the whole concert hall): Ah yes, she’s a KGB agent, come to scout out the situation!

Girl: Get out of my city and my country! I don’t give a damn about you, and you don’t scare me!

Movsar (to Abubakar): Shoot her.Then Abubakar took her by the arm, put her at the theater’s exit way (imagine a theater’s standard arrangement, where, close to the stage and to the left of the orchestra, there’s an exit leading out to the street that opens when a show or movie is through), and that’s where she was told to stand. The doors were opened a bit and Abubakar shot her point-blank. The girl fell to the floor dead. This was the only execution the entire concert hall witnessed. When they killed other people, they took them into the lobby, upstairs.

By the way, later on, they made some people who needed to use the restroom go to the one near where her body was lying. But I didn’t go.

Screenshot from television footage of Nord-Ost Siege. Police remove gassed hostages. Circulated anonymously online.

Do you have any advice for people who, God forbid, find themselves in a similar situation?

My advice is to remain calm, don’t lose your head, don’t succumb to their taunting, and don’t draw any attention to yourself. Well, don’t do these things, as much as it’s possible not to. If you think gas might be used, get a piece of cloth ready and try to figure out how you could wet it, if you needed to. But the main thing is to keep your head and not go out of your mind.

In the theater, there was one man who truly lost his mind. He suddenly jumped up and ran along the backs of the chairs, throwing an empty bottle of Coke at one of the terrorists. They fired at him a few times, missing him but hitting some of the other hostages who were sitting quietly. They caught him, of course, dragged him out from the hall, and executed him. The whole time, he was absolutely silent and looking around crazily in every direction. The whole thing was so stupid and absurd.

Can you tell us if any psychologists worked with you after all this? Are you able to attend the theater today for concerts? I think I’d never go to the theater another day in my life, if it were me. :(

I was fairly young back then—just a little over twenty. A month later, I was back at the Taganka Theater [in Moscow] with my family. I do remember being a bit off. My family, incidentally, didn’t understand how I was feeling, at all. They were just, like, “What’s going on?” And back then it wasn’t so much that I was scared, but that the confined space was weighing on me, and filled me with a sense of anxiety. Not to mention that the Taganka is a pretty drab theater, in terms of architecture. It was an interesting feeling to know that people just don’t understand how easily and tragically their entertainment can come to an end. And it’s all so easy—so many people relaxing in one place…

But if people really want to blow something up, they can blow up anything. I’m sure of this. And there’s nothing you can put at the entrances that will stop them. By the way, at the entrance of the Dubrovka theater on the night of the Nord Ost show, there were some very serious-looking guards. I remember them well. These days, I attend concerts and plays calmly enough, but I don’t go all that often.

There were psychologists while I was in the hospital. There was one woman who would talk to me, though I don’t know exactly who she was. She would just let me talk, and she’d listen. But I’ve already forgotten the details.

What was your attitude about the Chechen conflict before the hostage crisis? Did the experience change how you felt? (For example, did you want Russia’s troops to come straight home?) And what was your attitude afterwards and has it changed over the years?

As best I can remember, my attitude about Chechnya before Nord Ost was the same as everyone’s: yes, we need to wipe out all the terrorists. During the siege, my attitude became something entirely different. I thought, “They say it’s pointless going in there. Let them withdraw the troops. Let the Chechens live on their own, and we’ll be on own our, and there will be peace throughout the world. After we were freed, not immediately but gradually, I came to realize that the good side in this conflict really is Russia. Back then, I read a lot about the issue, talked with people about it, and took a big interest in the subject.

Whatever one makes of the Chechen conflict, I came to another important realization after Nord Ost. It’s something most people, not having lived through such an experience, never guess: the reality is that, somewhere right now, there are people willing to kill or maim you. You’d never guess it, but they already seriously hate you, just because you’re not of their faith and nationality. Or maybe it’s not that they hate you, so much as they don’t think of you as a human being. And often people still talk about the war in the Caucasus like it is something far away—like it’s something that never affects them personally. In fact, it’s all at our doorstep.

Anastasia Nikolaeva: ¿Estuviste ahí todo el tiempo?¿Estabas solo? ¿Qué pasó con el uso del gas? Si no me equivoco, ¿piensa que las fuerzas especiales rusas actuaron correctamente? ¿Cómo te ayudaron después?

Maksi2278: Sí, estuve ahí desde el inicio hasta cuando el teatro fue asaltado.

No estuve solo—estaba junto a dos amigas. Una de ellas murió. Su nombre era Masha Panova. Puedes buscarlo en Google. Mi otra amiga sobrevivió, y ahora está bien.

Usar el gas fue la decisión correcta, creo. Y pienso que nuestras fuerzas especiales se comportaron como verdaderos profesionales. Ciertamente, no vi el asalto en sí. Me desmayé. Lo último que recuerdo es cómo el humo empezó a esparcirse por el foso de orquesta, y el señor Vasiliev corrió hacia allá con un extintor de incendios. Todos pensaron que había habido un cortocircuito (había un baño en el foso de la orquesta y estaba bastante mojado).

Lo siguiente que recuerdo es despertar en cuidados intensivos en el Hospital Número 13. Clínicamente, yo en realidad morí, pero pudieron resucitarme.

En el hospital, todo el que pudo —incluso algunos pacientes— ayudaban. Estaba bastante cerca al Teatro —a corta distancia a pie, incluso— y es donde trajeron a la mayoría de rehenes [luegode que fueron rescatados]. Mi amiga fue llevada al Hospital Sklifosovsky, que queda mucho más lejos.

Así que todos estaban ayudando. Por ejemplo, estaban ayudando a llevar a la gente de un lugar a otro, y así sucesivamente. Cuando me desperté, había varios médicos a mi alrededor, y recuerdo que me moría por un vaso de agua y necesitaba usar el baño. Sin embargo, no podía usar una chata, y no podía llegar al baño por mi cuenta. Un par de médicas prácticamente tuvieron que llevarme sobre sus hombros al baño.

Luego de que pasaron unas cuantas horas, me empecé a sentir casi normal de nuevo. Me mantuvieron ahí por otro par de días, y luego me dieron de alta. El hospital fue acordonado. Incluso hubo hombres de las fuerzas especiales con armas automáticas en los pasillos.

Por lo que sé, no tomaron ningún rehén [en la sala de conciertos de París]. Los atacantes simplemente masacraron a los que estaban presentes. En el Nord Ost, a las autoridades no se les critica por asaltar el teatro propiamente, sino por fallar en salvar más rehenes, que en teoría podrían haber hecho.

Sí, eso es cierto, pero hubo varios docenas de luchadores experimentados en el Nord Ost, no cuatro jóvenes. Los terroristas del Nord Ost también minaron el teatro en su totalidad y controlaron no sólo la sala principal, sino el edificio entero y hasta un poco de la calle.

¿Las autoridades podrían haber salvado a todas las víctimas del gas? Quién diablos sabe. Aquí tiene que tener en cuenta la situación y la condición de los rehenes. De un lado, se necesita discreción total, y por Dios, no puede dejar que los periodistas olfateen las preparaciones para el asalto. De otro lado, los rehenes habían estado en el edificio por un largo tiempo, sentados en sillas incómodas en la misma posición, sin comida y sin siquiera agua suficiente. Por ejemplo, sólo me paré y fui al baño dos veces durante todo ese tiempo. Y el estrés fue absolutamente monstruoso, por supuesto. En otras palabras, todos estaban extremadamente débiles. ¿Las autoridades podrían haber tomado todo esto en cuenta? ¿Podría haber habido más ambulancias y primeros auxilios listos, con pistas despejadas, y suficientes médicos en la plantilla? Seguro, probablemente. Y quizás no. Al final, salvaron al 90% de los rehenes y eso es un éxito enorme. Tuvimos mucha suerte.

No fue la gente que organizó nuestro rescate o los médicos “lentos” que mataron a las víctimas —fueron los hombres y mujeres armados que vinieron a nuestra pacífica ciudad, a un teatro, para matar a civiles. ¿Sabías que la mayoría de las personas en la audiencia del teatro eran mujeres y niños?

Por supuesto, la situación [en la sala de conciertos en París] es muy diferente, pero el hecho es que tres de los cuatro terroristas se hicieron explotar, luego de que dispararan todas sus municiones a la multitud y a los policías. En otras palabras, el asalto contra estos hombres falló. Por supuesto, es imposible culpar [a la policía] por esto —pienso que hicieron todo lo posible.

Me parece que, sólo por los resultados, estos dos ataques terroristas son similares. Por supuesto que las situaciones fueron diferentes.

Captura de pantalla de imágenes televisivas del asedio de Nord-Ost. Circularon anónimamente en línea.

Quiero preguntarte: ¿viste algo de “humano” en los terroristas [que tomaron el Teatro Dubrovka]?

Sí, definitivamente vi algo de humanidad. Estaba sentado en la fila 15 en platea, y no lejos de mí se paró una joven terrorista suicida. Traté de hablarle, y un par de veces hasta me contestó, pero los mayores lo notaron y le dijeron algo, y dejó de responderme.

Recuerdo sus ojos. Luego, a menudo soñaba con ellos.

Le hablé a ella sobre dejar que las mujeres y niños se fueran: “¿Qué te han hecho ellos? Si te mueres por pelear, desquítate con las autoridades. Son ellos quienes empezaron esta guerra”.

A esto, ella dijo, “Nuestras familias —las familias de todos— han muerto en esta guerra que ustedes empezaron. No eran culpables de nada, tampoco, y había mujeres y niños entre ellos, también”.

Luego, dije, “Bueno, digamos que nos matan a todos ahora. ¿Puedes imaginar lo que el ejército ruso haría a continuación como represalia por nuestras muertes?” Y esto repentinamente tuvo un efecto en ella. Lo estaba pensando, y luego la hicieron desistir a gritos.

Había otro terrorista ahí, Yasser, quien circulaba con una máscara, y era una suerte de “policía bueno,” lo contrario a este matón total llamado “Abubakar”. Yasser habló a la gente como un ser humano normal, y escuchaba atentamente a las personas que, por ejemplo, estaban pidiendo algo en nombre de los enfermos. En cambio, si Abubakar decía algo, era sólo un conjunto de amenazas: les cortaremos la cabeza, todos van a morir, te odio, cerdo, y así sucesivamente. En la primera noche, mató a una joven. La hicieron parar en la salida y vació su arma automática en ella.

También recuerdo haber escuchado una conversación entre otros rehenes y una terrorista suicida. Ella tomó un celular de uno de los rehenes y dijo, “Hmm, esta cosa es genial. Qué bien que ustedes tienen esos teléfonos y nosotros no”. El caso es que, ella estaba verdaderamente impresionada y realmente pensaba que era “genial”. Esto es cuando los celulares aún eran realmente muy básicos.

Y estaba su líder, Movsar Barayev. Ahora, en ese entonces, estábamos completamente abrumados y no sabíamos que era Barayev. Sólo escuchamos que ellos lo llamaban “Movsar”. El nombre suena extraño a oídos rusos, y recuerdo pensar que era su sobrenombre —algo como “Mozart”. :) En general, estaba relativamente calmado —en la manera que se comportaba. No era particularmente rudo, y no mató ni golpeó a nadie.

Quizás así es como vimos que no todos los terroristas eran matones totales, y se pone en marcha el “Síndrome de Estocolmo”, y la gente empezó a creer que se podría llegar a un acuerdo con los terroristas y que todos podríamos sobrevivir, si en ese momento, pudiésemos enviar tan sólo un mensaje o hacer una sola llamada telefónica.

Te contaré sobre otro momento: luego de un asalto fallido al teatro (en la primera mañana, en cierta forma intentaron asaltar el edificio), hicieron estallar una pared en alguna parte y arrasaron con algunas ventanas, no en la sala de conciertos principal, sino en el área contigua. Y había una fuerte corriente de aire, y era muy fría. Los rehenes rogaron por ropa del guardarropa. Al final, [los terroristas] accedieron, y unos cuantos tipos trajeron los abrigos, y los dejaron en una pila donde estábamos sentados y empezaron a repartirlos.Vi mi abrigo y me paré, diciendo “Por favor, denme ése —es mi abrigo”. Luego, uno de los terroristas me hincó con su arma automática y dijo (textualmente): “Te las arreglarás sin él, camarada. Siéntate. Ya tienes suficiente”. :) Y en verdad yo estaba “vestido elegantemente”. Tenía un buen traje. :) No estoy seguro qué pueda concluir de eso, pero en el momento todos pensamos que fue muy gracioso, y la gente alrededor se rio bastante.

Y puedo contarte sobre otra ocasión: hubo un momento en la sala de conciertos principal, cuando de repente en la sala de radio (la ventana encima del auditorio, donde el operador del teatro se sienta) la emisión de noticias se detuvo y una canción bastante alegre de la banda Scooter empezó a sonar. Y la gente en el teatro empezó a animarse visiblemente —algunos incluso estaban cantando a coro. Pero, esto no duró, por supuesto.

Es simplemente imposible de imaginar: la gente vive, mientras hay vida aún, e incluso están cantando a coro con la radio… Leí sobre esto antes, pero nunca lo había escuchado directamente de un testigo presencial.

Bueno, estuvimos ahí por un largo tiempo. No dormimos y no comimos. Sólo estábamos sentados ahí y esperábamos. Principalmente fue entumecimiento y ataques de pánico, cuando pierdes la sensación en tus pies o se tiene una chispa de esperanza de que seríamos rescatados, y uno empezaba a retorcerse por todos lados. Uno empezaría a conversar tranquilamente con alguien al costado, pero pondrías tanta energía en hablar en un susurro, como la que normalmente usarías para gritar. Pensarías en todas tus opciones, escogerías cuidadosamente cada palabra, escucharías insaciablemente cada palabra que los terroristas pronunciaban y cada frase que podías oír de las noticias. Luego, la apatía retornaba, y de repente había más disparos. Por un momento, la gente caía al suelo entre las filas de asientos, y Barayev nos gritaba que permaneciéramos parados, de lo contrario ejecutarían a cualquiera que se agachara. Sin embargo, aún así todos se echaron al suelo. Fue como un instinto.

Captura de pantalla de imágenes televisivas del asedio a Nord-Ost. Circularon en línea anónimamente.

¿Te encontraste teniendo cualquier sentimiento de simpatía hacia los terroristas? Quizás algo como, “Diablos, esta chica es en realidad muy linda”. ¿Era la chica linda, por cierto?

Su rostro estaba cubierto. Sólo sus ojos eran visibles. Eran color avellana y hermosos. Era claro que ella era muy joven. Pero no sentí ninguna simpatía, excepto quizás hacia Yasser. Gracias a él, recibimos botellas de agua, por ejemplo. No sentí odio, tampoco. Solo sentí dos cosas: miedo y deseo de sobrevivir. Mi cerebro iba a cien millas por minuto, buscando maneras de vivir. Y las ideas más extrañas pasaban por mi mente: planes de escape, planes de juntar a todos los rehenes para atacar a los terroristas, e incluso una manera de dar a los terroristas lo que deseaban, para que nos dejaran ir.

Aunque tomaron los pasaportes de los hombres y revisaron nuestros registros de servicio militar. Si estaba en la reserva militar, significaba que serías primero en la línea para que te dispararan. Eso es lo que nos dijeron, entonces no había mucha esperanza de sobrevivir.

¿Hubo alguien que no tuviera pasaporte? ¿Qué les pasó a estas personas?

No sólo había personas sin pasaportes, sino también aquellos que los escondían. Algunos hombres tenían tarjetas militares, no pasaportes, y ellos los escondían o los desechaban. Vi algunas tarjetas militares tiradas en los puestos de la orquesta desde el balcón. ¿Sabes?, los terroristas prometieron ejecutar o decapitar en el acto a cualquier soldado o agente de la KGB.

En la práctica, si alguien no tenía su pasaporte, lo vigilaban y prometían matarlo después. Pero nunca terminaron haciéndolo. No hubo ejecuciones sin razones claras. Nunca reunieron valor para hacerlo, aunque al final estaban listos para empezar a ejecutar rehenes, justo antes de que la policía asaltara el teatro. Si la memoria no me falla, ellos querían dispararle a 10 personas cada hora. Sin embargo, no ejecutaron a nadie sin una razón.

¿Qué quiere decir “sin una razón”? Dispararon y mataron a una joven, dijo…

Bueno, si me preguntas, hubo una razón. Como me enteré después, la joven vino al teatro luego de que se enteró de la crisis de rehenes. La atraparon cerca de las puertas principales y la llevaron a la sala de conciertos, y la entregaron a Movsar Barayev, quien empezó a interrogarla delante de todos. Los terroristas pensaron que ella era una de las espía de FSB. Después nos enteramos de que era simplemente alguien que vivía cerca —en verdad, del edificio vecino. No obstante, nada de esto era claro entonces, y los terroristas no creyeron una sola palabra que ella dijo. Al mismo tiempo, hizo toda una demostración de resistencia y valentía, actuando como si estuviera al borde de la histeria.

El diálogo fue algo así:

Movsar: ¿Quién eres y por qué has venido?

Joven: ¿Y quién es usted y por qué ha venido a mi ciudad?

Movsar (a toda la sala de concierto): Ah sí, ¡ella es una agente de la KGB, que ha venido a enterarse de la situación!

Joven: ¡Váyase de mi ciudad y de mi país! ¡Usted me importa un bledo y no me asusta!

Movsar (a Abubakar): Dispárale.Luego Abubakar la tomó del brazo, la situó en una de las salidas del teatro (imagina una disposición estándar de un teatro, donde, cerca del escenario y a la izquierda de la orquesta, hay una salida que lleva a la calle que se abre cuando el espectáculo o película ha terminado), y ahí es donde le dijeron que se parase. Las puertas estaban abiertas ligeramente y Abubakar le disparó a bocajarro. La joven cayó muerta al suelo. Esta fue la única ejecución que la sala de conciertos entera presenció. Cuando mataron a otras personas, las llevaron al vestíbulo, en el piso de arriba.

Por cierto, más adelante, hicieron que algunas personas que necesitaban usar el baño fueran al que estaba ubicado cerca de su cuerpo. Pero yo no fui.

Captura de pantalla de imágenes televisivas del asedio de Nord-Ost. La policía retiró a los rehenes afectados por el gas. Circularon anónimamente en línea.

¿Tienes algún consejo para las personas que, no permita Dios, se encuentren en una situación similar?

Mi recomendación es que se mantengan calmados, que no pierdan la cabeza, no sucumban a las provocaciones, y no llamen la atención hacia ustedes. Bueno, no hagan esas cosas, lo más que sea posible no hacerlo. Si piensas que quizás se use gas, ten algo de ropa lista y trata de encontrar la manera de humedecerla, si lo necesitaras. Pero lo más importante es mantener la calma y no volverse loco.

En el teatro, había un hombre que verdaderamente se volvió loco. De repentem saltó y corrió a lo largo de los respaldos de las sillas, arrojando una botella vacía de Coca Cola a uno de los terroristas. Le dispararon unas cuantas veces, no le dieron, pero los tiros hirieron a otros rehenes que estaban sentados tranquilamente. Lo atraparon, por supuesto, lo arrastraron fuera de la sala y lo ejecutaron. Todo ese tiempo, estuvo callado y mirando en toda dirección como loco. La situación entera fue estúpida y absurda.

¿Puede decirnos si algún sicólogo trabajó contigo luego de todo esto? ¿Puedes asistir a un concierto en un teatro ahora? Pienso que yo nunca iría más a un teatro en mi vida, si fuera tpu. :(

Yo era bastante joven en ese entonces —tenía un poco más de veinte años. Un mes después, regresé al Teatro Taganka [en Moscú] con mi familia. Sí recuerdo sentirme un poco fuera de lo normal. Mi familia, casualmente, no podía entender en absoluto cómo me sentía. Ellos me preguntaban: “¿Qué pasa?” Y en ese entonces, no era tanto que estuviese asustado, sino que el espacio reducido me preocupaba y me daba ansiedad. Sin mencionar que el Taganka es un teatro bastante sombrío, en términos de arquitectura. Fue una sensación interesante saber que las personas sencillamente no entienden lo fácil y sencillamente que su diversión puede llegar a su fin. Y todo es tan sencillo —tantas personas relajándose en un lugar…

No obstante, si la gente quiere hacer estallar algo, puede hacer estallar cualquier cosa. Estoy seguro de eso. Y no hay nada que pueda poner en las entradas para detenerlos. Por cierto, a la entrada del Teatro Dubrovka en la noche del espectáculo de Nord Ost, había unos guardias bastante serios. Los recuerdo bien. En estos días, voy a conciertos y espectáculos lo suficientemente calmado, pero no voy tan seguido.

Había sicólogos cuando estuve en el hospital. Había una mujer que me hablaba, pero no sé exactamente quién era. Ella simplemente me dejaba hablar, y me escuchaba. Pero ya me he olvidado los detalles.

¿Cuál fue tu actitud sobre el conflicto checheno antes de la crisis de rehenes? ¿La experiencia cambió tu manera de pensar? (Por ejemplo, ¿querías que las tropas rusas volvieran directamente a casa?) ¿Y cuál fue tu actitud después y ha cambiado con los años?

Si mal no recuerdo, mi actitud respecto a Chechenia antes de Nord Ost fue la misma que la de todos: sí, tenemos que eliminar a todos los terroristas. Durante el asedio, mi actitud se tornó totalmente distinta. Pensé: “Ellos dicen que no tiene sentido entrar ahí. Déjenlos retirar las tropas. Dejen que los chechenos vivan por sí solos, y nosotros por nuestra parte, y habrá paz alrededor del mundo». Luego de que fuimos liberados, no inmediatamente, pero gradualmente, me di cuenta de que el lado bueno en este conflicto, realmente es Rusia. En ese entonces, leí un montón sobre el tema, hablé sobre eso y tomé un gran interés.

Lo que sea que uno piense sobre el conflicto checheno, me di cuenta de otra cosa importante después de Nord Ost. Es algo que la mayoría de personas, no habiendo pasado por tal experiencia, no imaginan: lo cierto es que, en alguna parte ahora, hay personas dispuestas a matarte o mutilarte. Nunca lo adivinarías, pero ya te odian en serio, tan sólo porque no tienes su fe o su nacionalidad. O quizás no es tanto que ellos te odien como que ellos no piensan en ti como un ser humano. Y a menudo la gente aún habla sobre la guerra en el Cáucaso como si fuera algo lejano —como si fuera algo que nunca les afecta personalmente. En realidad, todo está en el umbral de nuestra puerta.