El vestíbulo del Trident Hotel en Port Antonio, Jamaica, muestra una de las pinturas de Stanley. Este hotel en concreto posee 22 de sus obras. Foto cortesía del artista. Usada con permiso.

El artista de origen británico y residente en Jamaica, Mike Stanley, cuya muestra individual Passion for Paint, ha llegado a su fin esta semana en el campus Mona de la Universidad de las Antillas, habló con Global Voices sobre sus primeras influencias en Londres, su traslado a Jamaica a finales de los 80 y el entorno tropical que ha dejado huella en su obra.

Global Voices (GV): Ud. prefiere llamarse «pintor» antes que artista. ¿Por qué y cuándo nace esta distinción?

Mike Stanley (MS): I have been a practicing painter since I was a student at Chelsea College of Arts in London (1963 – 67). It’s always been what I do. When people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m a painter. There was the explosion of ‘abstract expressionism’ in New York in the late 1950s, when European artists moved to the United States after World War II. Jackson Pollock was a great abstract expressionist painter. Then there was ‘post-painterly abstraction’, which involved greater use of color. In 1960s London, we had a ‘European take’ on that style. This is how my style developed, through the influence of these artists; my style has always retained the notion of paint as a language. These days, though, paint is regarded as ‘old hat’.

Mike Stanley (MS): He sido pintor practicante desde que estudié en el Chelsea College of Arts de Londres (1963 – 67). Es lo que siempre he hecho. Cuando la gente me pregunta lo que hago les digo que soy pintor. Cuando el expresionismo abstracto eclosionó en Nueva York a finales de los 50, los artistas europeos se trasladaron a Estados Unidos después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Jackson Pollock fue un gran pintor del expresionismo abstracto. Después llegó la «abstracción postpictórica», que entrañaba un mayor uso del color. En el Londres de los 60 nos dieron unas «dosis europeas» sobre este estilo. Así fue como, a través de las influencias de esos artistas, desarrollé un estilo que aún conserva la idea de la pintura como lenguaje. Sin embargo, hoy se la considera anticuada.

GV: Cuéntenos sobre su vida artística en Londres. ¿Cómo fueron los comienzos?

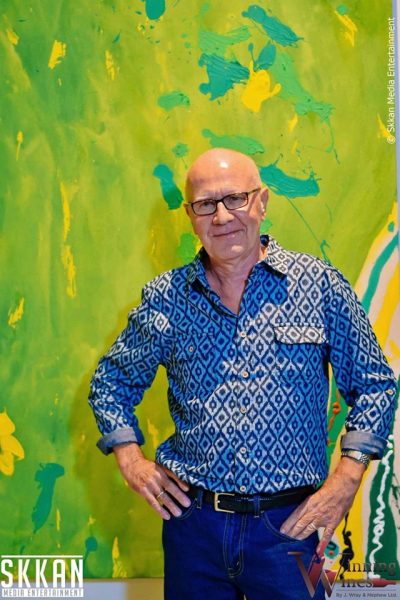

El pintor Mike Stanley en una reciente exposición en el edificio principal regional de la Universidad de las Antillas, un espacio estupendo para el arte. Foto cortesía del artista. Usada con permiso.

MS: I started exhibiting while I was still a student at Chelsea. I won second prize in a student exhibition in 1966 called ‘Young Contemporaries’. I won 50 Pounds. I spent my prize money on driving lessons. I continued to paint throughout the '70s and '80s, supporting myself by teaching. I have never been a ‘dyed in the wool’ teacher, but I have to give thanks for the income, which allowed me to keep painting. I always say the best thing about teaching is the students.

During that period, painting became a kind of subversive activity. There was little support from the art establishment in London; the art gallery scene was all to do with ideas — conceptual art. Some art schools even stopped teaching the traditional skills of painting, drawing and sculpture. I went my own way. It was not easy being an artist in London — and there were many of us, exhibiting in warehouses and the like. We were ‘family’ — one big family of people who used paint.

MS: Empecé a exponer cuando todavía era estudiante en Chelsea. En 1966 quedé segundo en una exposición estudiantil llamada Young Contemporaries. El premio fueron 50 libras que gasté en clases de conducir. Continué pintando en los 70 y los 80 y me ganaba el sustento enseñando. Nunca he sido un maestro consagrado, pero tengo que dar gracias por el dinero, que me permitió seguir con la pintura. Siempre digo que lo mejor de la profesión de enseñar son los alumnos.

Durante este periodo, la pintura se convirtió en un tipo de actividad subversiva. Recibíamos poco apoyo del establishment de las artes londinense. El mundo de las galerías se impregnaba de ideas sobre arte conceptual. Algunas escuelas dejaron de enseñar las técnicas tradicionales de pintura, dibujo y escultura, pero yo seguí mi propio camino. No era fácil ser un artista en Londres, la mayoría exponíamos nuestro trabajo en almacenes y lugares así. Éramos como una familia, una gran familia de gente que trabajaba con la pintura.

GV: ¿Quién fue su mayor influencia en Inglaterra? ¿Quién le inspiró para seguir pintando?

MS: I had a great teacher, John Hoyland, from my first year at Chelsea onwards. He was a part of the art establishment and had quite a high profile career. His teaching wasn’t at all formal; he taught through telling stories. He was also very funny — we used to bust up with laughter, even to the point of tears. Although his paintings were great, what I really learned from him was an attitude.

MS: Tuve un gran maestro, John Hoyland, desde el primer curso en Chelsea hasta que terminé. Él formaba parte del establishment y con una carrera respetable. Sus clases no eran ni mucho menos académicas, enseñaba contando historias. Era también muy divertido, se nos saltaban las lágrimas de risa con él. Aunque sus pinturas eran estupendas, lo que aprendí realmente de él fue actitud.

GV: ¿Qué le motivó para irse a vivir a Jamaica?

MS: I came to Jamaica in 1988 with my second wife Margaret, who is a Jamaican textile artist, and our two year-old daughter Suzi. Margaret had always kept in touch with her Jamaican family, and we had paid several long visits. At the time, we were both teaching in the UK; it was our bread and butter. Then we were both made redundant by Maggie Thatcher! We arrived in Jamaica with the idea of trying it out for a couple of years. I was drawn to Kingston, because you aren’t seen as a tourist here, you can be yourself — 28 years later, we are still here.

MS: Vine a Jamaica en 1988 con mi segunda esposa Margaret, una artista jamaiquina de las artes textiles, y Suzi, nuestra hija de dos años. Margaret nunca perdió el contacto con su familia y les hicimos varias visitas prolongadas. En aquel tiempo, los dos éramos maestros en el Reino Unido. La enseñanza era nuestra forma de ganarnos la vida. ¡Luego ambos fuimos despedidos por Margarita Thatcher! Llegamos a Jamaica con la idea de intentarlo un par de años. Kingston me atrajo porque aquí no te ven como un turista, puedes ser quien eres, y 28 años después todavía seguimos aquí.

GV: ¿Se adaptaron fácilmente a su nueva vida?

MS: Well, it wasn’t easy making a living, teaching and painting in Jamaica. So I used to supplement my income by traveling to the UK to do supply teaching, every summer. I did this for more than ten years; it kept us going.

MS: Bueno, no era fácil ganarse el sustento, tener que enseñar y pintar a la vez, así que obtenía ingresos extras viajando al RU y dando clases allí todos los veranos. Lo hice durante más de diez años y eso nos permitió salir adelante.

MS: Sus pinturas tienen brillo y mucho color. ¿Qué significa el color para Ud.?

MS: Well, you know, this annual trip, from Jamaica to the UK, made me recognize the huge difference in the light. The way you see color changes. As you fly into the UK, the colors are muted. The light changes completely. It’s more natural to me to be colorful in my work. I always embraced color; I used to call myself the ‘Gauguin of West Norwood'! Many European artists’ work became more colorful when they moved south — for example, Delacroix, Van Gogh. The environment affects you.

MS: Pues verá, este año el viaje de Jamaica al Reino Unido me ayudó a reconocer la enorme diferencia que hay en la luz. El modo en que ves los colores cambia. Cuando vuelas al RU los colores mutan, la luz es totalmente otra. Para mí es más natural utilizar el color en mis obras. Siempre acepté los colores y me llamaba a mí mismo el «Paul Gauguin» de West Norwood. Las obras de muchos artistas europeos se volvieron más coloridas cuando se fueron a vivir al sur (por ejemplo, Delacroix y Van Gogh). El entorno acaba por transformarte.

GV: ¿De qué manera se han influenciado entre sí, como artistas, Ud. y su esposa?

MS: Margaret’s work has always been a big influence on me. She has always channelled tropical imagery and color in her work. I would say her influence has increased over the years. Now — especially in my latest exhibition — I am leaning more towards semi-figurative art, myself.

MS: La obra de Margaret siempre me ha influenciado mucho. En su obra ha sabido canalizar las imágenes tropicales y los colores. Diría que su influjo ha aumentado con los años. Ahora, y sobre todo en mi última exposición, estoy inclinándome más hacia el arte semifigurativo.

GV: Ahora que vive en Jamaica, ¿qué le gusta más hacer con su profesión artística?

MS: I am doing more big paintings again. I hadn’t done any big paintings for some time. But when I saw the Matisse exhibit at the Tate Modern in 2014, there were these huge cutout pictures. I thought, ‘I’ve got to do more big paintings’. By the way, you can see many of my large-scale works at the Trident Hotel in Port Antonio; they bought 22 of my paintings. Perhaps my early work at an architecture office in London inspired my large pieces — I am interested in public spaces. Now, funnily enough, I am teaching art at the Caribbean School of Architecture at the University of Technology in Kingston. Back to where I started!

Since I have been living here, I have exhibited on average every two years. I have had three large one-man exhibitions, roughly every ten years, with smaller ones in between and some joint exhibitions with Margaret.

MS: Vuelvo a pintar cuadros grandes. No los había pintado durante algún tiempo, pero en la exposición Matisse de 2014 en el Tate Modern fue cuando vi esos enormes recortes y pensé: «tienes que pintar más cuadros de este tamaño». Por cierto, podéis ver la variedad de mis obras en el Trident Hotel en Port Antonio. Ellos me compraron 22 de mis pinturas. Quizá mis primeras obras en un estudio de arquitectura de Londres sirvieron de inspiración para mis piezas más grandes. Me interesan los espacios públicos. Aunque parezca cosa de risa, doy clases de arte en Caribbean School of Architecture en la Universidad Tecnológica de Kingston. ¡He vuelto a los inicios!

Desde que vivo aquí he expuesto como promedio una vez cada dos años, y cada diez años más o menos he hecho tres grandes exposiciones individuales, con otras menores en medio y algunas exposiciones conjuntas con Margaret.

GV: Para terminar, ¿qué piensa del actual estado del arte de Jamaica?

MS: When we first arrived here, the art seemed like watered-down versions of what we had seen elsewhere. This was because many were trained outside Jamaica. Then David Boxer brought the (self-taught) Intuitives to public attention at the National Gallery of Jamaica — something so unique to Jamaica, something I’d never seen before. Younger Jamaican artists nowadays have more ambition, more professionalism. They have a more international approach, but they still retain a very Jamaican ‘twist’ — like Matthew McCarthy, who used to paint signs; and Leasho Johnson, a painter and graphic artist. The National Gallery of Jamaica has taken a more international approach in recent years, representing many different strands of contemporary art.

MS: Cuando llegamos por primera vez, su arte me pareció una versión aguada de lo que habíamos visto en otros sitios, debido a que muchos no se habían formado en Jamaica. Luego, David Boxer acercó (en plan autodidacta) el arte intuitivo al público en la National Gallery de Jamaica, algo excepcional en este lugar y que yo nunca había visto. Los artistas jamaiquinos más jóvenes muestran hoy más ambición y profesionalidad. Tienen también una visión más internacional, pero todavía conservan gestos muy del país, como Matthew McCarthy, que pintaba carteles, y Leasho Johnson, pintor y artista gráfico. La National Gallery of Jamaica ha adoptado un enfoque más internacional en los últimos años, representando muchas corrientes distintas del arte contemporáneo.